Dear Robert Steuckers, you are among the few West European journalists or publicists who profoundly understand the history and geopolitics of Russia. We know each other now since more than fifteen years and that’s why I find this interview is important. First of all, would like to introduce yourself, to tell us about your profession, your specialisation, your titles, etc. ?

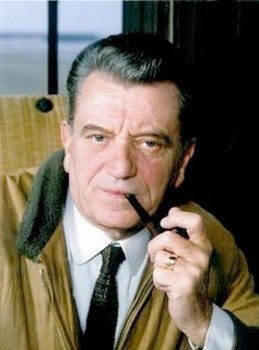

RS: Well, there is nothing special about me. I was born in Uccle/Ukkel in January 1956 in a quite poor family. My father was the son of a peasant having a family of seven children and came to Brussels to find a job as a servant in 1933. He didn’t want to go to school to become a schoolmaster, didn’t want to work on the farm feeding the pigs and couldn’t find a long-lasting job in his province. My mother, who died recently in December 2011 at the age of 97, was the daughter of a beer brewer and seller, who, at the age of 14, left his village, where his own father had also seven children and only one cow he had to drive along ways and paths in his village in order to let her graze as he had no meadow of his own.

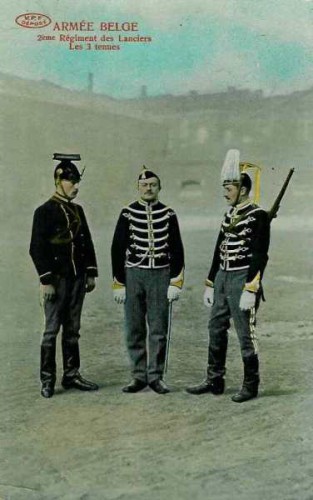

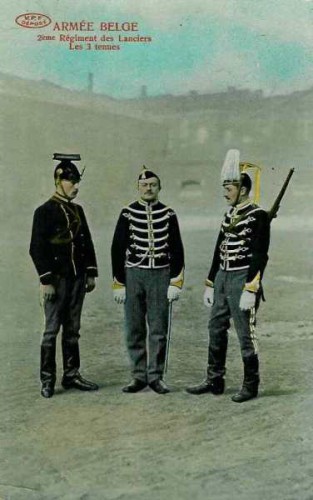

In Brussels my grand-father became the helper of a baker and then could be hired by the army to replace a rich son of a bourgeois family, who had no lust to do his military service (at that time conscription was not yet compulsory in Belgium). He served for three years in the 2nd and 4th Lancers, an elite light cavalry regiment, in which he got the noble attitude in his daily gestures he kept till his last breath, almost 87 years old. With the money he got from the rich family to do military service instead of the son of the house, he could buy and take over the small business of a retired or passed away brewer and marry my grandmother in 1908, the very year one of his sisters migrated to the United States, to Indiana, to run a farm with her husband: they too had seven children. My mother’s parents started a trade in beers and lemonades, which lasted 80 years, being taken over by my uncles in 1953. My grand-parents’ youngest son retired in 1988. My grandfather was called up in August 1914 and participated in the First World War as a sergeant in the transport units behind the Yser Front in Flanders. He swallowed mustard gas (Yperite), suffered ten years long from the effects of this nasty chemical but could recover after a terrible pneumonia, due to lung complications, in 1928. Even if he could earn a good life by selling beers to pubs and private customers, he was the model of an ascetic, eating almost no meat, only oats with milk and eggs, together with rhubarb and prunes that he cultivated in his own garden. He wanted to remain thin to mount horses in case if… but he had no horse anymore. He bought motorcars and lorries that he was never able to drive himself: this was the task of his sons. He used to say: “Modern times are preposterous: they all need a motor under their bottom even for a distance less than 500 yards”. My grandmother was even more ascetic and left me one of her often quoted saying: “Clock hours (i. e. measured time) are for fools, the wise know their time” (‘t Uur is voor de zotten, de wijzen weten hun tijd”). In this sense, she was exactly in tune with the celebrated German writer Ernst Jünger, when he theorized his ideas about time.

In Brussels my grand-father became the helper of a baker and then could be hired by the army to replace a rich son of a bourgeois family, who had no lust to do his military service (at that time conscription was not yet compulsory in Belgium). He served for three years in the 2nd and 4th Lancers, an elite light cavalry regiment, in which he got the noble attitude in his daily gestures he kept till his last breath, almost 87 years old. With the money he got from the rich family to do military service instead of the son of the house, he could buy and take over the small business of a retired or passed away brewer and marry my grandmother in 1908, the very year one of his sisters migrated to the United States, to Indiana, to run a farm with her husband: they too had seven children. My mother’s parents started a trade in beers and lemonades, which lasted 80 years, being taken over by my uncles in 1953. My grand-parents’ youngest son retired in 1988. My grandfather was called up in August 1914 and participated in the First World War as a sergeant in the transport units behind the Yser Front in Flanders. He swallowed mustard gas (Yperite), suffered ten years long from the effects of this nasty chemical but could recover after a terrible pneumonia, due to lung complications, in 1928. Even if he could earn a good life by selling beers to pubs and private customers, he was the model of an ascetic, eating almost no meat, only oats with milk and eggs, together with rhubarb and prunes that he cultivated in his own garden. He wanted to remain thin to mount horses in case if… but he had no horse anymore. He bought motorcars and lorries that he was never able to drive himself: this was the task of his sons. He used to say: “Modern times are preposterous: they all need a motor under their bottom even for a distance less than 500 yards”. My grandmother was even more ascetic and left me one of her often quoted saying: “Clock hours (i. e. measured time) are for fools, the wise know their time” (‘t Uur is voor de zotten, de wijzen weten hun tijd”). In this sense, she was exactly in tune with the celebrated German writer Ernst Jünger, when he theorized his ideas about time.

My father came to work as a servant to the House of Count Willy (Guillaume) de Hemricourt de Grunne in 1938. In the summer of this year he made his first trip outside Belgium to a village in Franche-Comté, near the Swiss border, where Count de Grunne had inherited a wonderful mansion house from an aunt who had inherited it from his own grandfather, the French Catholic thinker and politician Count Charles de Montalembert. I still spend some days in this part of Europe twice or three times a year. In August 1939, just a few days after the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, my father was called up in the Belgian army, was sent to barracks near the German border during the phoney war, then to the Beverloo military camp, where he underwent the German air attack by Stuka bombers in the early morning of May 10th, 1940. After his duty, as no Flemish conscript soldiers were taken prisoner of war and sent to Germany, my father went back to the House of Count de Grunne, where he worked till his retirement in 1978. Some months later Willy de Grunne died, just three days before his 90th birthday.

My youth was spent in the marvellous surrounding Willy de Grunne created in the large garden behind his house in Brussels, which was a marvel of architecture designed by the genial Belgian architect Brunfaut in the early Twenties. Willy de Grunne wanted to have different flowers in his garden in spring, summer and late summer, so that I always could play among the most beautiful selection of plants that a team of very able professional gardeners kept with love and care. The mansion in Franche-Comté is still a marvel today and is now run by his grandson, whose father was Russian and son of a White Guard officer and later one of the best teachers of your language in Belgium. The surroundings created by Willy de Grunne made of me a youth completely immune to the seductions of modern world, but simultaneously I was perhaps also affected by a serious handicap: I could never understand the way of working in factories or offices, with the artificial rhythms and hierarchies they imply.

The world of my youth was a world with only personal, friendly relationships never determined by contracts, only by pure genuine human and manly confidence, based on the given word you never withdraw. Books were important in this world, as Willy de Grunne had, among other tasks as a diplomat, to read books for Queen Elizabeth Wittelsbach, a Bavarian Duchess, who became Queen of the Belgians in 1909. Willy de Grunne was Grand Master of her House in the Thirties. Queen Elizabeth was, just as her whole Bavarian family in Munich, an excellent sponsor of arts, music and museums. We owe her the Egyptology Museum in Brussels and among many other things the world famous “Concours Reine Elizabeth”, promoting young talented musicians from all over the world. Many young Russian musicians participated in this prestigious competition. Besides, Queen Elizabeth has been (and still is) criticized for being of German origin and for having refused to boycott the USSR and China during the Cold war. She ended her life in the Fifties and the early Sixties by acquiring the then sulphurous reputation of a “Bolshevik Queen”. She died in 1965.

The world of my youth was a world with only personal, friendly relationships never determined by contracts, only by pure genuine human and manly confidence, based on the given word you never withdraw. Books were important in this world, as Willy de Grunne had, among other tasks as a diplomat, to read books for Queen Elizabeth Wittelsbach, a Bavarian Duchess, who became Queen of the Belgians in 1909. Willy de Grunne was Grand Master of her House in the Thirties. Queen Elizabeth was, just as her whole Bavarian family in Munich, an excellent sponsor of arts, music and museums. We owe her the Egyptology Museum in Brussels and among many other things the world famous “Concours Reine Elizabeth”, promoting young talented musicians from all over the world. Many young Russian musicians participated in this prestigious competition. Besides, Queen Elizabeth has been (and still is) criticized for being of German origin and for having refused to boycott the USSR and China during the Cold war. She ended her life in the Fifties and the early Sixties by acquiring the then sulphurous reputation of a “Bolshevik Queen”. She died in 1965.

Now, I became a so-called “intellectual” thanks to my father’s sister Julienne, who had a diploma of schoolmistress, had married Hendrik Lambrechts, a Flemish schoolmaster in ‘s Gravensvoeren (Fouron-le-Comte), and had a son, Raoul, who after his father’s death in 1949, became a political scientist having studied at the prestigious University of Louvain, after brilliant secondary school studies (Latin and Greek) achieved at the Flemish “Heilig Hart College” (“Sacred Heart College”) in Ganshoren near Brussels. My aunt was very proud of her son. But unfortunately Raoul died in 1961 from a heart disease that would now be easily cured. I was only five years old when I was brought to the University Hospital in Louvain to see him dying after a previous operation that provoked a blood clot that stroke his brain. The vivid and awful memory of this dying unconscious young man, his desperate eyes and the frightful calls of his mother remain in my mind till now. After Raoul’s death my father was told and even ordered by his sister to make all the efforts needed to let me study at a University, because, she said, “our old Province Limburg should have an elite born out of peasant families”. I was given the task, even the burden, to replace Raoul in the family: a man had been killed, another had to take his place. Aunt Julienne died in 1991. I saw her some days before her passing away. She was as happy as happy can be. A bright smile illuminated her face, although she was suffering a lot due to the dog days: finally, not only me, the crazy boy full of silly fantasies, had something like a diploma, but also the daughter of her daughter, who just got her diploma of political scientist at the State’s University of Ghent. One of my cousins found the right words when she held a very well balanced speech in the church on her burial day: “A grand and simple lady”.

These family circumstances explain why I was first sent to a good primary school in the part of the City where I’ve always lived. The teachers were severe and taught us parsing very well, which has been of the uttermost importance for my further studies in Latin in the secondary school and in German, English and Dutch for my studies at University or at the Translators’ and Interpreters’ School. After the usual six years of primary school, I was sent to a secondary school not far from home, where my father, after a good briefing of Aunt Julienne and of Willy de Grunne, let me be registered in the Latin classes. I couldn’t understand why I had to study Latin when we both went to this impressive old school to meet a friar responsible to register the new pupils. He told me when I asked him why Latin was for that a secondary school is like a train with several cars, that my seat had been booked in the Latin car and if after a year or a couple of years I couldn’t feel well in this kind of luxury or first class car, they would book a seat for me in another one, perhaps less prestigious but even more efficient and pragmatic. But I immediately liked to study Latin, especially words and etymologies, and never failed any examination in this subject. My crux during the years of my secondary school had been maths not because I had a prejudice against maths —on the contrary— but because in September 1967, some crazy and criminal minds had decided to introduce “modern math” (singular!) without any pedagogical preparation: modern math is indeed too abstract to understand for children younger than 12 or 13 years and I was only 11 when I started secondary school. I was saved at the end of the first year because fortunately some clever minds had rung the alarm bell and imposed algebra in the traditional way.

During the fifth year, the so-called Latin “poetry class”, I became firmly decided to learn modern languages, more precisely German and English at University. After two years I changed for the Translators and Interpreters School, which was not far from my home. After four years I got the diploma of English and German translator. To obtain it I had to translate and comment a book of Ernst Topitsch and Kurt Salamun criticizing “ideologies” as constructed systems that prevent real pragmatic thoughts to develop or that serve as crushing instruments to perpetuate the domination of false elites (like the pigs in Orwell’s Animal Farm) becoming gradually out of touch.

So I became successively a clerk by Rank Xerox (to answer calls in several languages), the dumbfound redaction secretary of Benoist’s magazine “Nouvelle école” (having had the privilege to analyse on the very field the preposterousness of the all business lead by this silly old wet blanket of Benoist), a soldier doing his military service in the 7th Company Logistics for ten short months in Saive (near Liège), in Marche-en-Famenne, in the marvellous Burg Vogelsang and the village of Bürvenich in Germany along the border, a freelance translator and interpreter for twenty years (with a lot of different customers active in all possible social fields), a sworn translator for the Ministry of Justice, a private teacher, one among the numerous freelance assistants of Prof. Jean-François Mattei, who published in 1992 the “Encyclopédie des Oeuvres philosophiques” for the “Presses Universitaires de France”, and, as a wonderful and enthralling hobby, the metapolitical fighter you’ve known since now more than fifteen years. As a metapolitcal fighter, I was first a young and second-rank animator of the Brussels’ GRECE-group around Georges Hupin, an occasional pen pusher for his small bulletin “Renaissance Européenne” (still published nowadays as the organ of Vial’s “Terre & Peuple” movement in the French-speaking part of Belgium), then the founder of “Orientations”, the redaction secretary of “Nouvelle école”, one of the founders of the Brussels’ EROE–group, the founder of “Vouloir” together with Jean E. van der Taelen, a speaker having wandered throughout Europe to address meeting or participate to seminars of all kinds, a member of Faye’s “Etudes & recherches”-club within the “nouvelle droite”, then the organiser together with others of the Munkzwalm-seminars in Flanders, one among the founders of “Synergies Européennes” (together with Gilbert Sincyr and Jean de Bussac) and organisers of all the activities lead by this European group, including the publication of “Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes” and “Au fil de l’épée”.

You have a universal outlook that can be called encyclopaedic. How did you get your education? Whom can you consider your teachers? Who are the authors and which are the books that have influenced you most?

If once in your life you decide to become a metapolitical fighter you have of course as a duty to read ceaselessly and to acquire willy-nilly this “encyclopaedic outlook” you talk about. Moreover if the metapolitical purpose you follow is to re-establish European culture in all its richness the piles of books awaiting you reach permanently the ceiling. I got my education at school and nowhere else. It would be dishonest and conceited to invent a story trying to demonstrate somehow the contrary. Schoolbooks for the subject “History” were and are still good in Belgium. You have simply to assimilate the contents and to complete them with further readings. Of course, I owe a lot to our Latin teacher Simon Hauwaert and our philosophy teacher Lucien Verbruggen, not only for their lessons but also for the long tours they organized for us in Greece and Turkey, in order to discover Ancient Greek civilisation. When I was sixteen and a half, I was brought by the circumstances of these long school trips in the streets of Athens or Istanbul and visited Ankara’s Hittite Museum just one day after having had a short tour around Cappadocia’s cave dwellings and Byzantine churches. This was an even so good training in fact than school curriculum in itself. Another good thing was that we had to prepare every year for Hauwaert and his successor Salmon a paper on a classical Latin topic together with a grammatical analysis of an original text (I had with my late friend Leyssens, a future gynaecologist, who died in a mountain accident at 42 leaving three orphan sons, to study successively Lucretius’ De rerum naturae, a part of Plinius’ Natural History and Plautus’ theatre). The last year Rodolphe Brouwers, our French and History teacher, compelled us to write a paper on history: I had to write a survey about the COMECON countries (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Rumania, Hungary). Brouwers had also the good idea to let us parse in all details Bossuet’s speeches in order to let us discover the good balance of a possible barrister’s plea or to be able later to coin speeches along the same stylistic guidelines in order to let them be better understandable only by giving them a well-balanced rhythm à la Bossuet. It has been very useful each time the GRECE-people asked me to address their annual meeting held in Paris or Versailles. During a first year at University, I followed the lectures of René Jongen in German grammar and had a course of German literature by the Flemish writer Paul Lebeau. Later I had English grammar by Jacques Van Roey, as well as good introductory lectures in history, among which the ones of Léopold Génicot on the West European Middle Ages were the most memorable. At the interpreters’ school, two years later, we had excellent practical trainings in modern languages.

What concerns the specific New Right literature I was deeply influenced by Pierre Chassard’s introduction to Nietzsche’s philosophy (“Nietzsche, finalisme et histoire”), which compelled me to read Nietzsche more critically and to be definitively defiant in front of all kinds of ready-made idealistic notions (the ready-made “Platonisms” that lards unrealistic political programs) and to know that moralistic arguments are too often escapism and rejection of plain common sense. I had already read Nietzsche’s “Antichrist” and his “Genealogy of Moral” but I had then as a boy of 14 or 16 no serious guidelines to understand actually the purposes Nietzsche had by writing this two cardinal books. In 1970, when I was in the 3d class, I asked my French teacher Marcel Aelbrechts which novels I had to read: all he suggested me was excellent but the main book in the series was undoubtedly the “Spanish Testament” of Arthur Koestler: so I got fascinated by English novels not through the English teacher (who at that time was also an excellent man, Mr. Mercenier) but through the French teacher, an old mischievous friar, who was certainly not sanctimonious (and with whom I had a real boxing fight at the end of my studies because he tried to prevent me to beat the math teacher; we nevertheless remained good friends; normal people fight and shout at each other: the political correctness says today that such attitudes are wrong but in no other period of history so many people had to look for the help of the psychiatrist or to swallow sedating pills; so “political correctness”, as we can objectively state, is surely bad for your health…).

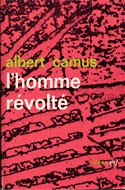

My next French teacher was Jacques Goyens, who is now retired of course and considered nowadays as a main French-speaking Belgian author. He introduced us to poetry (Rimbaud, Leconte de Lisle, Baudelaire, Verlaine,…) and to present-day literature. During springtime 1972, Jean-Paul Leyssens and I worked on Albert Camus and we stressed mainly his philosophical ideas, inspired by Nietzsche and written down in “L’homme révolté”. Goyens was disappointed because we had coined a portrait of Camus as a Nietzschean philosopher and therefore neglected his main contribution to the genuine French literature of the Fifties. But in the end I was happy to have learned about the philosophical dimension of Camus’ work and Goyens was perhaps thoroughly right as Camus is more important as a writer than as a philosopher, but what both parties forgot was the rather complex context in which Camus’ political views developed at the time when existentialism was fashion in Paris. In March 1973, Goyens took us away from school to visit an important exhibition at the Belgian Royal Museum of History and Archaeology: it was about the glorious medieval period of the so-called Rhine-Meuse civilization between the 9th and the 15th centuries. This region is indeed the cradle of the Western Imperial tradition, as the reaction against the Merovingian decay (our first “Smuta”) took place in the area between Meuse, Rhine and Mosel among the Pippinide clan of Charles the Hammer (Charles Martel) and as Charlemagne settled his main capital in the City of Aachen, from where a kind of Renaissance of Ancient thought took place long before the more widely known Italian Renaissance of the 15th Century. I was just seventeen then but the idea that our own imperial cradle was so near to my place fascinated me especially as my father’s family is from Flemish Limburg, an area close to this fertile and green cradle county. Jean Thiriart too liked to stress that his family originated from the Walloon part of this Rhine-Meuse area and that therefore the European idea was his own as the Carolingian Imperial idea had been the one of his ancestors.

My next French teacher was Jacques Goyens, who is now retired of course and considered nowadays as a main French-speaking Belgian author. He introduced us to poetry (Rimbaud, Leconte de Lisle, Baudelaire, Verlaine,…) and to present-day literature. During springtime 1972, Jean-Paul Leyssens and I worked on Albert Camus and we stressed mainly his philosophical ideas, inspired by Nietzsche and written down in “L’homme révolté”. Goyens was disappointed because we had coined a portrait of Camus as a Nietzschean philosopher and therefore neglected his main contribution to the genuine French literature of the Fifties. But in the end I was happy to have learned about the philosophical dimension of Camus’ work and Goyens was perhaps thoroughly right as Camus is more important as a writer than as a philosopher, but what both parties forgot was the rather complex context in which Camus’ political views developed at the time when existentialism was fashion in Paris. In March 1973, Goyens took us away from school to visit an important exhibition at the Belgian Royal Museum of History and Archaeology: it was about the glorious medieval period of the so-called Rhine-Meuse civilization between the 9th and the 15th centuries. This region is indeed the cradle of the Western Imperial tradition, as the reaction against the Merovingian decay (our first “Smuta”) took place in the area between Meuse, Rhine and Mosel among the Pippinide clan of Charles the Hammer (Charles Martel) and as Charlemagne settled his main capital in the City of Aachen, from where a kind of Renaissance of Ancient thought took place long before the more widely known Italian Renaissance of the 15th Century. I was just seventeen then but the idea that our own imperial cradle was so near to my place fascinated me especially as my father’s family is from Flemish Limburg, an area close to this fertile and green cradle county. Jean Thiriart too liked to stress that his family originated from the Walloon part of this Rhine-Meuse area and that therefore the European idea was his own as the Carolingian Imperial idea had been the one of his ancestors.

In the translators’ and interpreters’ school we had good grammar and lexicology teachers like Potelle, Van Hemeldonck and Defrance (who had had a tremendously active life and had founded one of Belgium’s more prestigious bookshop in Ostend before becoming a teacher and who brought us to Berlin in 1977 and to Munich in 1978 during two memorable students’ trips). What concerns more specifically geopolitics and history, the lectures of Mrs. Costa, based on a German official handbook, whose title was “Zweimal Deutschland”, provided us a thorough knowledge in recent German history, which is the key to understand the process of geopolitical and political alienation in Europe after 1945. The history lectures of Prof. Peymans stressed the political and philosophical specificity of the liberal and subversive Western hemisphere (Britain, USA, France), which, in order to be able to develop, had to get rid of all the traditional institutions generating the peoples’ identity or of all the “atavistic forces” as Solzhenitsyn called them while he was defending old Russia against all the endeavours of the wild Westernization you have endured in your country. During the two last years in the translators’ school, we had lectures in international politics and current affairs given by Mrs. Massart, who agreed to let me comment and introduce Jordis von Lohausen’s book on geopolitics. My destiny as a “geopolitician” within the New Right groups was settled once for all. Having read the German “geo-economicist” Anton Zischka about Eastern Europe in order to be able to write out Brouwers’ history paper in 1974, my non Western vision of European history was from then on quite complete, as Mrs Costa’s lectures on recent German history, Zischka’s nostalgia of a united European area without any Iron Curtain and Lohausen’s Central European vision of history and geography made me immune for all strictly Western or NATO world visions.

As I’ve already told it to our Scandinavian friends in an interview they submitted me, historical atlases were important for me, among them I want to quote the “DTV-Atlas zur Weltgeschichte” and Colin MacEvedy’s British atlases issued by the celebrated Penguin publishing house in Harmondsworth, England.

You know some European languages and make a lot of translations. Why didn’t you study Russian or any other Slavonic language?

I’ve got a diploma for the English and German languages. As we spoke Dutch and French at home and more generally in Brussels’ everyday life, I was quasi born as a bilingual boy. My school education was in French as most of the Flemish schools disappeared in the late Forties and early Fifties because the Germans had supported a policy of “Rückgermanisierung” or “re-Germanization” during their second occupation. After 1945, the “Germanization” policy, that had been launched through the financial support for a revival of the Flemish language, was of course cancelled and the Belgian establishment inaugurated a policy of “Rückromanisierung”, that decelerated later because people started to send their children back to Flemish schools again, mostly because they weren’t attended by so many immigrants. This phenomenon of “Rückromanisierung” was especially the case in the Southern municipalities of Brussels. My cousin Raoul could attend a Flemish high quality secondary school in the Northern part of the urban area. An education in French was not as such a bad thing, of course, but we thought anyway that, even if French is a very important world language, the policy of “French alone”, followed by some Frenchified zealots within the Belgian establishment in Brussels lead to a kind of closeness or isolation, as Dutch/Flemish is a excellent springboard to learn English, German and Scandinavian languages. The left liberal and socialist Flemish author August Vermeylen, at a time between 1890 and 1914 when socialism in Belgium wasn’t uprooted (and an uprooting force as well) and produced excellent and original cultural goods, used to say that we had to be Flemings again in order to become good Europeans (in Nietzsche’s meaning of the phrase). Vermeylen didn’t exclude French as a language of course but wanted people to open their minds to the cultural worlds of Britain, Holland, Germany and Scandinavia. In this sense I am a socialist à la Vermeylen. And my own boy went to a Flemish school, despite the fact that his mother was born in Wallonia and had to learn Dutch as an adult.

To learn Slavonic languages at the time of the Cold War was almost impossible as you couldn’t meet native speakers in common professional and everyday life surroundings. When I was eleven years old in summer 1967, just after having achieved primary school, I went to de Grunne’s place in Franche-Comté, where he had invited “Babushka”, the grand-mother of his grand-children. “Babushka” was a fantastic elderly woman, who taught the Russian language to her grand-sons and I helped her to keep them and bring them to a playing area with a toboggan in the village. During these afternoons, only Russian was spoken! About more than one year later, I went for the first time in my life to a real theatre (i. e. not a wandering theatre for school children) to watch an adaptation of Dostoievski’s “Crime and Castigation”, written by Alexis Guedroitz, de Grunne’s son-in-law, and masterly performed by the troupe of the famous Belgian actor Claude Etienne, who played the role of the investigating police principal. This was not the only Russian presence in my childhood: the wife of our neighbour was Russian and I played as a boy with their half-Russian children. More: her father, a former Colonel of the Czar, had an old batman, a giant and handsome mujik, who worked in their little shop producing children disguises for carnivals and fancy fairs, as they had to make a living when they came back like many White Russians completely ruined from Congo where the Belgian authorities had sent them before this Central African country became independent. This former corporal batman of the White Army was fascinated by the little boy I was because —I disclose it here for the first time as I’ve always been too shy to tell it— I had been elected in 1958 the most beautiful baby boy of Belgium: this has been my very first diploma but since then I grew old and ugly! As a simple man, the old Russian White Gardist was very proud to be the neighbour of the most beautiful baby boy of Belgium and once a week this poor penniless man bought for me a bar of chocolate in our street’s sweets shop and put it in the letter box. My mother told me that this was a real sacrifice for such a poor man and taught me to respect sincerely this modest and kind weekly gesture of gentleness. But I kept in mind that all simple Russian men were generous and not avaricious, so I always have picked up denigrating propaganda, be it the German one of WWII or the NATO one of the Cold War, with an extreme scepticism.

When I moved to Forest again in 1983, my neighbour was the celebrated nurse Nathalia Matheev, daughter of another Czarist officer, who died fighting the Red Army in Crimea. She was loved by all our neighbours and died just a few days before my son was born. In her flat, where I live now, many Russians of the Twenties’ emigration came to pay her a visit, especially on Easter Day, when “Paska” and vodka with fruit juice were served: among them a cousin of Admiral Makharov and the German-Baltic Count von Thiesenhausen, who at Nathalia’s burial mass, stood upright at the respectable age of 83 during three long hours, holding a candle and singing the old sweet Slavonic burial songs, without a single minute of rest. Nathalia studied nursery in Brussels after having left Russia and was even sent as a volunteer of the Belgian Red Cross to Peru to manage a health centre high in the Andean mountains in 1928.

I tried by my own to learn Russian through an Assimil method when I was sixteen in 1972. I discovered Indo-European comparative etymology in our reference schoolbook “Vocabulaire raisonné Latin-Français” of the Belgian Latinist Cotton, where you could find the roots of all the Indo-European basic vocabulary, so I was inclined at that time to start studies of comparative linguistics and I decided shortly before the Easter holiday that I traditionally spent at the Flemish sea resort of De Haan, together with the future gynaecologist Leyssens, whose grand-father had a house there. I stayed alone in a charming and cheap hotel as my father loathed to spend weeks at the sea side: he was a land peasant unable to understand the importance of the sea, “a space you cannot cultivate and whose water is salty and undrinkable for men and cattle”. Every morning and every evening, after a complete day outside by foot or by bike even under the rainy and cold skies of the West-Flemish coastal district in March or April, I studied a lesson of Russian, another of Welsh and a third one of Swedish, in order to discover a Slavonic, a Celtic and a Teutonic language that I didn’t know. This was of course silly —a crazy idea of a funny teenager— as you cannot study such a spectrum of languages by your own without a well-established didactic frame and able teachers. So the experience didn’t last long. At the translators’ school, I started a Danish course but the extremely sympathetic lady, in charge of these lectures, died two weeks later and we had to wait for some weeks or months to find a new teacher, who came only at the very end of the academic year. In 2008, I was offered a free course of Russian but this initiative, due to several reasons, collapsed rapidly, chiefly because it couldn’t match into the scheduled and compulsory school activities.

So at the time of the Cold war, it was easier to learn German and English, two languages that are closer to our own Dutch and Flemish, in their official varieties as well as in their many dialects. I could have a better and direct access to these languages than to Slavonic or Celtic languages. In a speech held at the very beginning of the academic year 1976 (the day the underground train of Brussels was inaugurated), Alexis Guedroitz told the assembled teachers and students that Russian was a language that you can only acquire properly “with your own mother’s milk”. To study correctly a subject implies not to get rid of the quality of “otium”, giving you time and pleasure and banking on pieces of knowledge you already and naturally have, avoiding at the same time painful efforts that could spoil your life and degenerate into “negotium”, i. e. the feverishness of a greedy businessman who is never satisfied of what the gods give him. If I can read —and not properly speak— Latin languages is due to the fact that Simon Hauwaert was a very demanding Latin teacher. Shortly before my grand-father died in December 1969, I only had experienced a couple of years in the Latin classes and discovered next to his old worn-out and brownish armchair a copy of “Oggi”, a popular Italian magazine —I still cannot imagine how this magazine arrived there as my grand-father couldn’t understand a single word of Italian— and stated that I could understand for my own many sentences, thanks to the efforts of our Latin teachers (Philippe, Dumont, Salmon). Later, when Georges Hupin opened in 1979 a first office for the New Right/G.R.E.C.E. branch in Brussels, I could read copies of Marco Tarchi’s leading bulletin “Diorama Letterario” and of Pino Rauti’s weekly “Linea”, which were among the best the movement produced in Western Europe at that time. So I decided to try as much as possible to understand and translate the articles. I took the opportunity between January and October 1982, when I was out of work and had to wait to be enlisted in the army, to study the general features of Italian and Spanish, in order to acquire at least a passive knowledge of these languages; the purpose of this superficial studying was to get able to gather as much information as possible from Southern European publications in order to feed the New Right magazines with original stuff. What concerns Portuguese texts, I had been spoilt by the publisher of “Futuro Presente”, the New Right quarterly issued in Lisbon at that time. He came regularly to Paris, when I worked for “Nouvelle école” there in 1981. We often had the opportunity to have meals together. I helped myself to read these magazines with a copy of an Assimil method for Portuguese and an old dictionary.

We started our cooperation at the time you published “Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes” and animated the groups called “European Synergies”. Would you like to remind us the history of this organisation? How did it start?

As you know it, I had been active in several “New Right” initiatives in Belgium and France since 1974 and became a member of the GRECE-group in September 1980 after having followed a special summer course in July 1980, which took place in Roquevafour in Provence. I worked for “Nouvelle école” during nine months in 1981, came back to Belgium in December 1981 to do my military service and started, with the help of Jean E. van der Taelen, to activate a club in Brussels, that was called “EROE” (“Etudes, Recherches et Orientations Européennes”) in order to be completely independent from the Parisian coterie around Alain de Benoist and of course to be protected from all the quarrels and campaigns of hatred he used to rouse against his own friends and partners, especially against Guillaume Faye. From August to December 1992, I stated that cooperation with the crazy Parisian pack would be quite impossible to resume even in the very next future and that all type of further collaboration with them meant a waste of time, a time we would have spent arbitrating quarrels between new and former friends of Benoist or defending ourselves against preposterous gossip. After I had left the 1992 summer course in Roquefavour earlier, as I was fed up with the quarrels between de Benoist and GRECE-Chairman Jacques Marlaud, who, after having been insulted in the worst of all possible ways, was supposed to be prosecuted next to me in front of a Court composed of Benoist himself, a stuck-up simpleton and a snitch called Xavier Marchand and the usual godawful yesman Charles Champetier (nicknamed “His Master’s Voice”). Marchand had to play the role of the Prosecutor; he tried to make an angry face but was very nervous, his jackass’ look betraying obviously the fact that he was playing a part that had previously been dictated to him. As a good bootlicker pupil, he did his homework with application and started to accuse Marlaud and myself, first to have given articles to Michel Schneider’s magazine “Nationalisme & République”, an activity that had been forbidden a posteriori, and second to have started a non very accurately defined “plot” in favour of Schneider (who had no intention at all to plot against the Parisian bunch but only wanted to give a new life to the group he once founded, the CDPU [= “Centre de Documentation et de Propagande Universitaire”], of which my old friend Beerens was the correspondent in Brussels). After Marchand’s vociferated speech, I simply asked him to repeat his accusation. He resumed his clumsy plea but the contents of the second version were slightly different than the ones of the first version: poor simpleton Marchand hadn’t learned properly by heart his lesson… I said: “Which is the correct version? If it’s version B, then version A is false and…”. Benoist, Marlaud and Marchand, all nonplussed by this apparently harmless question, started immediately to shout loudly at each other, giving the very amusing spectacle that a quarrel between Frenchmen always is, while Champetier remained silent and was blowing the smoke of his cigarette up the air. After they all had uttered their grievances loudly, they left the backyard, where the trial should have taken place, and only Benoist followed me, repeating ceaselessly that “he liked me” while he walked heavily with his flat feet through the marshy meadow next to the river flowing along the park where the Summer course’s beautiful old mansion stood, disturbing the siesta of a good score of frogs and toads, that jumped away, cawing clamorously, to escape the hooves of this huge approaching pachyderm blowing a nasty gas cloud of cigarette smoke. I left the summer course, telling cocky Marchand, who had made a cock–up of the wannabe trial, that he should find immediately a car to travel to Aix-en-Provence. As he of course asked me why, I said that he had to buy an Assimil method to learn German, as I was about to leave and as he had of course to replace me as a translator for the German group. He had exactly a couple of hours to become fluent in German.

I decided to leave definitively in December after they refused to pay me back the copies of my magazines that had been sold during the annual meeting, as well as the ones of “The Scorpion” Michael Walker had asked me to sell for him. I had already the impression to be a clown in a awkward circus but if this role implied to lose permanently money, it was preferable to leave once for all the stage. I had the intention to devote myself to other tasks such as translating books or private teaching. This transition period of disabused withdrawal lasted exactly one month and one week (from December 6th, 1992 to begin January 1993). When friends from Provence phoned me during the first days of 1993 to express their best wishes for the New Year to come and when I told them what kind of decision I had taken, they protested heavily, saying that they preferred to rally under my supervision than under the one of the always mocked “Parisians”. I answered that I had no possibility to rent places or find accommodations in their part of France. One day after, they found a marvellous location to organise a summer course. Other people, such as Gilbert Sincyr, generously supported this initiative, which six months later was a success due to the tireless efforts of Christiane Pigacé, a university teacher in political sciences in Aix-en-Provence, and of a future lawyer in Marseille, Thierry Mudry, who both could obtain the patronage of Prof. Julien Freund, the most distinguished French heir of Carl Schmitt. The summer course was a success. But no one had still the idea of founding a new independent think tank. It came only one year later when we had to organise several preparatory meetings in France and Belgium for a next summer course at the same location. Things were decided in April 1994 in Flanders, at least for the Belgians, Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese and French. A German-Austrian team joined in 1995 immediately after a summer course of the German weekly paper “Junge Freiheit”, that organized a short trip to Prague for the participants (including Sunic, the Russian writer Vladimir Wiedemann and myself); people of the initial French team, under the leading of Jean de Bussac, travelled to the Baltic countries, to try to make contacts there. In 1996, Sincyr, de Bussac and Sorel went to Moscow to meet a Russian team lead by Anatoly Ivanov, former Soviet dissident and excellent translator from French and German into Russian, Vladimir Avdeev and Pavel Tulaev. We had also the support of Croatians (Sunic, Martinovic, Vujic) and Serbs (late Dragos Kalajic) despite the war raging in the Balkans between these two peoples. In Latin America we’ve always had the support of Ancient Greek philosophy teacher Alberto Buela, who is also an Argentinian rancher leading a small ranch of 600 cows, and his old fellow Horacio Cagni, an excellent connoisseur of Oswald Spengler, who has been able to translate the heavy German sentences of Spengler himself into a limpid Spanish prose. The meetings and summer courses lasted till 2003 and the magazines were published till 2004. Of course, personal contacts are still held and new friends are starting new initiatives, better adapted to the tastes of younger people. In 2007 we started to blog on the net with http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com in seven or more languages with new texts every day and with http://vouloir.hautetfort.com and http://www.archiveseroe.eu/ only in French with all the articles in our archives. This latest initiative is due to a rebuilt French section in Paris. These blogging activities bring us more readers and contacts than the old ways of working. As many people ask to read my own production, mostly students in order to write some short chapters in their papers or to be able to write out proper footnotes, I decided in October 2011 to publish my own personal archives on http://robertsteuckers.blogspot.com/

What are the main goals of “Synergies Européennes”?

Now the very purposes of “Synergies Européennes” or “Euro-Synergies” were to enable all people in Europe (and outside Europe) to exchange ideas, books, views, to start personal contacts, to stimulate the necessity of translating a maximum of texts or interviews, in order to accelerate the maturing process leading to the birth of a new European or European-based political think tank. Another purpose was to discover new authors, usually rejected by the dominant thoughts or neglected by old right groups or to interpret them in new perspectives.

“Synergy” means in the Ancient Greek language, “work together” (“syn” = “together” and “ergon” = “to work”); it has a stronger intellectual and political connotation than its Latin equivalent “cooperare” (“co” derived from “cum” = “with”, “together” - and “operare” = “to work”). Translations, meetings and all other ways of cooperating (for conferences, individual speeches or lectures, radio broadcasting or video clips on You Tube, etc.) are the very keys to a successful development of all possible metapolitical initiatives, be they individual, collegial or other. People must be on the move as often as possible, meet each other, eat and drink together, camp under poor soldierly conditions, walk together in beautiful landscapes, taste open-mindedly the local kitchen or liquors, remembering one simple but o so important thing, i. e. that joyfulness must be the core virtue of a good working metapolitical scene. When sometimes things have failed, it was mainly due to humourless, snooty or yellow-bellied guys, who thought they alone could grasp one day the “Truth” and that all others were gannets or cretins. Jean Mabire and Julien Freund, Guillaume Faye and Tomislav Sunic, Alberto Buela and Pavel Tulaev were or are joyful people, who can teach you a lot of very serious things or explain you the most complicated notions without forgetting that joy and gaiety must remain the core virtues of all intellectual work. If there is no joy, you will inevitably be labelled as dull and lose the metapolitical battle. Don’t forget that medieval born initiatives like the German “Burschenschaften” (Students’ Corporations) or the Flemish “Rederijkers Kamers” (“Chambers of Rhetoric”) or the Youth Movements in pre-Nazi Germany were all initiatives where the highest intellectual matters were discussed and, once the seminary closed, followed by joyful songs, drinking parties or dance (Arthur Koestler remembers his time spent at Vienna Jewish Burschenschaft “Unitas” as the best of his youth, despite the fact that the Jewish students of Vienna considered in petto that the habits of the Burschenschaften should be adopted by them as pure mimicking). Humour and irony are also keys to success. A good cartoonist can reach the bull’s eye better than a dry philosopher.

In 1997, Anatoly Ivanov, a Russian historian, polyglot and essayist registered the Russian branch of the “European Synergies” in Moscow. How did you learn about him?

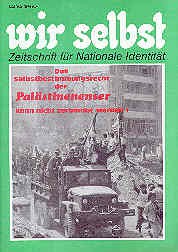

I don’t remember quite well but I surely read some sentences about him and his work in an article of Wolfgang Strauss, who wrote an impressive amount of articles, essays and interviews about Russian affairs in German and Austrian magazines as Criticon, Aula, Junges Forum, Staatsbriefe, Mut, Europa Vorn, etc. The closest contact I had at that time was with the team of Junges Forum in Hamburg, which also published next to Strauss’ essays a monthly information bulletin called DESG-Inform (DESG meaning “Deutsch-Europäische Studiengesellschaft”). In this context, I received a copy of a German translation of his very important book Logika Koshmara (Logik des Alptraums) published in 1993 in Berlin with a foreword and a conclusion of Wolfgang Strauss, explaining the world view of the new Russian dissidents, who were not ready to exchange communism for the false values of the West. After the publishing of Logik des Alptraums, Ivanov was regularly quoted in the DESG bulletin or in Strauss’ long and accurate essays in Staatsbriefe. But the very first contact I had was a letter by Ivanov himself, in which he introduced himself and sent some comments that we translated or reproduced for Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes or Vouloir. After having received this letter, I phoned him, so that we could have a vivid conversation. The rest followed. But I am sad that I never could meet him till yet.

The same is true for Strauss: I should like to remember here that the very first German article I summarized for Hupin’s Renaissance Européenne was a Strauss’ contribution to Schrenck-Notzing’s Criticon about the neo-Slavophile movement in Russia. I met Strauss only once and too briefly: at a Summer Course of the German weekly magazine Junge Freiheit near the Czech border in the region of Fichtelgebirge in 1995. The representative of Russia was then Vladimir Wiedemann, whose speech I translated for Vouloir.

Since then our magazines ‘Heritage of the Ancestors” and “Atheneum” have published news about the “European Synergies”, some of your articles in Russian translation and reviews about such publications as “Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes”, “Vouloir”, “Nation Europa”, “Orion”, etc. Do you find such an initiative important? Why?

It is indeed important to inform people about what happens in the wide world. The pages “Atheneum” dedicates to the activities of other groups in Europe or elsewhere in the world replace or complete usefully the information formerly or still communicated by DESG-Inform, Diorama Letterario, Nation Europa, Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes, etc. Recently, i. e. in the first days of June 2011, when I was interviewed in Paris for the free radio broadcasting station “Méridien Zéro”, the two young journalists declared to regret the lack of information about what is said, published or broadcast in the so-called “New Right” or “Identitarian” movements throughout Europe, since “Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes” ceased to be published. They both found that the ersatz of it on the Internet was not sufficient, although one of them produces every week, depending on the topics they are dealing with, an excellent survey of webpages, books and magazines on the “Mériden Zéro’s” website. The same kind of intelligent survey should be done regularly for books because there is one big difference between the time, when the New Right began to develop at the end of the Sixties and in the Seventies, and now: many topics aren’t taboo anymore, such as geopolitics or Indo-European studies at scientific level. Lots of books on the main topics the New Right wanted to rediscover at the time when such topics were repressed are nowadays issued by all possible publishing houses and not only by clearly identifiable conservative or rightist publishers. For general news on current affairs, we can bank on a German friend to issue monthly a general survey of interesting topics gathered from the German press and on a Flemish friend for the same purpose, but this time twice or three times a week. The Flemish “Krantenkoppen” (= “papers’ heads”) are in four languages (Dutch, French, German and English). You can jump into the web to discover them regularly by paying a visit to : http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/. In Italian you can get daily a excellent collection of articles on http://www.ariannaeditrice.it/. A good survey of the American non conformist press and webpages can be found on Keith Preston’s site : http://www.attackthesystem.com/. But you and the Méridien Zéro journalists are right: the instrument should be widened and rationalized. This one important goal to reach for all those who were formerly confident of the “Synergies Européennes” network.

You also published articles and interviews of us all in the bulletin “Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes” and in the journal “Vouloir”. Had these texts some echo? Who among your readers did pay more attention to our material and about Russian matters in general? Was it Wolfgang Strauss, Jean Parvulesco or Guillaume Faye?

All our readers agreed that our articles about Russia or Russian authors and our interviews of Russian personalities were of the uttermost importance. Strauss and Parvulesco received the magazines regularly. I had regular contacts with Parvulesco, who unfortunately died in November 2010 (cf. The category “Jean Parvulesco” on http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com ), and I know that he always read attentively everything coming from Russia: one should not forget that Parvulesco was among the first thinkers in France who were aware of the dangers epitomized by Brzezinski’s strategic projects in Central Asia and elsewhere, be it along the “New Eurasian Silk Road” or in the Caucasian and Pontic areas. Articles like “La doctrine des espaces de désengagement intercontinental” and “De l’Atlantique au Pacifique” (and within this important geopolitical manifesto, the paragraphs under the subtitle “Zbigniew Brzezinski et la ligne politico-stratégique de la Chase Manhattan Bank” – Both texts can be read in “Cahier Jean Parvulesco”, Nouvelles Littératures Européennes, 1989).

All our readers agreed that our articles about Russia or Russian authors and our interviews of Russian personalities were of the uttermost importance. Strauss and Parvulesco received the magazines regularly. I had regular contacts with Parvulesco, who unfortunately died in November 2010 (cf. The category “Jean Parvulesco” on http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com ), and I know that he always read attentively everything coming from Russia: one should not forget that Parvulesco was among the first thinkers in France who were aware of the dangers epitomized by Brzezinski’s strategic projects in Central Asia and elsewhere, be it along the “New Eurasian Silk Road” or in the Caucasian and Pontic areas. Articles like “La doctrine des espaces de désengagement intercontinental” and “De l’Atlantique au Pacifique” (and within this important geopolitical manifesto, the paragraphs under the subtitle “Zbigniew Brzezinski et la ligne politico-stratégique de la Chase Manhattan Bank” – Both texts can be read in “Cahier Jean Parvulesco”, Nouvelles Littératures Européennes, 1989).

But at a first stage, we have to thank retrospectively the guy who translated Russian texts under the pseudonym of “Sepp Staelmans” (a “Bavarianification & Flemishification” of “Josef Stalin”!). He came to us, when he was sixteen and we all were still students, and asked to our friend Beerens what he could do for the movement: Beerens, who in this very evening had most probably drunken too much red wine, told him: “You should learn German and Russian!”. Incredible but nevertheless true: the young lad did it! Many other translations were done by girls who were trainees in my own translation office. More students indeed study Slavonic languages now than formerly, simply because there is no Iron Curtain anymore and they can meet youth of their own age in Slavonic countries. Michel Schneider, who once published the interesting political magazine “Nationalisme et République”, stayed in Moscow for a quite long time and sent us articles too. The former readers of Schneider’s magazine welcomed heartedly of course the Russian stuff he sent to us.

One day in Paris, just after having jumped out of the train from Brussels, I had a meal in the famous “Brasserie 1925”, just in front of Paris’ “Gare du Nord”, with a young lady, an incredibly attractive and intelligent woman seeming to come just out of the most beautiful fairy tale. She belonged to the team around the most efficient French present-day Slavists, such as Anne Coldefy, Lydia Kolombet or Marion Laruelle. They wanted to have copies of all our publications dealing with Russian topics for their archive.

Many other articles or essays on Russian matters were inspired by German books of Slavistics produced by the publishing house Otto Harassowitz in Wiesbaden. This publishing house is indeed specialized in Russian ideas and topics and issues regularly a thick journal called Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte (= “Studies on East European History”), where we could find many inspiring texts.

Can we call our own initiatives as belonging to the transnational “New Right” movement? How would you define this ideological movement? Who are its leaders?

The phrase “New Right” has of course many different significations. Especially in the Anglo-Saxon world it can delineate a rather multiple-faced libertarian movement inspired by Reaganomics, Thatcherite British conservatism, i. e. an renewed form of the old liberal Manchesterian way of managing a country’s economy, etc. The main theoreticians who inspire such a British or Transatlantic view of politics, state or economics are Milton Friedman, Friedrich von Hayek or Michael Oakshott. This is not, of course, the way we would define ourselves as exponents of a “New Right” (although in some particular aspects, beyond economics as such, Hayek’s notion of “catallaxy” is interesting).

Personally I would say that I belong to a synthesis of 1) the German “Neue Rechte”, as it had been accurately defined by Günter Bartsch in his book “Revolution von Rechts?”, 2) of the French “nouvelle droite” as it has been coined by Louis Pauwels, Jean-Claude Valla and Alain de Benoist at the end of the Sixties and 3) of the Italian initiatives of, first, Pino Rauti and his weekly paper “Linea”, and, second, of Dr. Marco Tarchi and his journals “Diorama letterario” and “Trasgressioni” before they started sad aggiornamenti in order not to be insulted by the press.

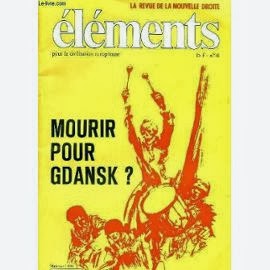

The German “Neue Rechte”, as defined by Günter Bartsch, is a bio-humanist movement, opposed to technocracy in the widest sense of the word, has got a biological-medical view on man (on anthropology). This implies the rather well-known option for ethnopluralism, which, subsequently, implies an option for all kinds of “liberation nationalism”, within and outside Europe, and for a broad conceived “European Socialism”. The story of the French “nouvelle droite” is better known throughout the world due to the many essays or books written about it since more or less four decades but not so much has in fact been written about the link between, on one hand, the early G.R.E.C.E.-Groups and, on a second hand, Louis Pauwels, editor of the futurology and prospective journal “Planète”, the organized “Groupes Planète” throughout France’s regions, the specific interpretation of the May 1968 ideology of Herbert Marcuse that had been developed in the numerous essays of the magazine, the critical approach of Western materialism, the speculations of Arthur Koestler about biology (“The Ghost in the Machine”) and his attraction towards parapsychology, the influence of the Gurdjieff group on the all venture, the presence in the redaction team of the Belgian thinker Raymond De Becker with his particular interpretation of Jung’s psychoanalysis (and his past as a “crypto-fascist” activist in the Thirties and the Forties, afterwards fascinated by Jungian psychoanalysis during the seven years he spent in jail). Moreover, “Planète” was in a certain way “ethnopluralist” as it supported the Occitan revival in Southern French regions such as Provence and Languedoc. Purpose was of course to dismantle the materialistic and rationalist Jacobine French State. From my experience in the New Right groups, I consider as essential the following topics: the metapolitical way of working, the critical view on the Western world (developed in a special issue of “Nouvelle école” on America and a remarkable issue of “Eléments” on the “Western civilization”), the exploration of the German Conservative Revolution through thinkers like Spengler, Jünger, Moeller van den Bruck or Carl Schmitt.

The German “Neue Rechte”, as defined by Günter Bartsch, is a bio-humanist movement, opposed to technocracy in the widest sense of the word, has got a biological-medical view on man (on anthropology). This implies the rather well-known option for ethnopluralism, which, subsequently, implies an option for all kinds of “liberation nationalism”, within and outside Europe, and for a broad conceived “European Socialism”. The story of the French “nouvelle droite” is better known throughout the world due to the many essays or books written about it since more or less four decades but not so much has in fact been written about the link between, on one hand, the early G.R.E.C.E.-Groups and, on a second hand, Louis Pauwels, editor of the futurology and prospective journal “Planète”, the organized “Groupes Planète” throughout France’s regions, the specific interpretation of the May 1968 ideology of Herbert Marcuse that had been developed in the numerous essays of the magazine, the critical approach of Western materialism, the speculations of Arthur Koestler about biology (“The Ghost in the Machine”) and his attraction towards parapsychology, the influence of the Gurdjieff group on the all venture, the presence in the redaction team of the Belgian thinker Raymond De Becker with his particular interpretation of Jung’s psychoanalysis (and his past as a “crypto-fascist” activist in the Thirties and the Forties, afterwards fascinated by Jungian psychoanalysis during the seven years he spent in jail). Moreover, “Planète” was in a certain way “ethnopluralist” as it supported the Occitan revival in Southern French regions such as Provence and Languedoc. Purpose was of course to dismantle the materialistic and rationalist Jacobine French State. From my experience in the New Right groups, I consider as essential the following topics: the metapolitical way of working, the critical view on the Western world (developed in a special issue of “Nouvelle école” on America and a remarkable issue of “Eléments” on the “Western civilization”), the exploration of the German Conservative Revolution through thinkers like Spengler, Jünger, Moeller van den Bruck or Carl Schmitt.

The Italian magazines were more interested in pure political sciences, even in some popularized articles from “Linea”, describing mostly the life of important and original political figures and of political scientists (such as Pareto, Mosca, Sombart, Weber, Sorokin, etc.) and explaining the main trends of their works. For us in Belgium the critique the Italian fellows developed to reject partitocracy was more interesting than the French or German ideas or debates. Why? Simply because the corrupted situation in which we lived and still live, the impossibility to realise genuine political programmes and an authentic reformation aiming at solving actual problems was very similar to what happened and still happens in Italy: in France, De Gaulle had made it possible to escape the narrowness of the 4th Republic’s petty politics and had suggested original ideas such as the workers’ participation, the “intéressement” of a factory’s personnel in the benefits of their company or a new form of Senate with representatives of the regions and the professions and not with aloof professional politicians, who could after some years of parliamentary life become totally cut from all social realities. Nothing of all these intelligent projects after him became reality but nevertheless at the end of the Seventies, there was still hope to translate these seducing programmes into French political life. In Germany at that time, the full results of the post war reconstruction could be felt and at that time the country didn’t experiment the impediments generated by the many dissolving consequences of a partitocratic system.

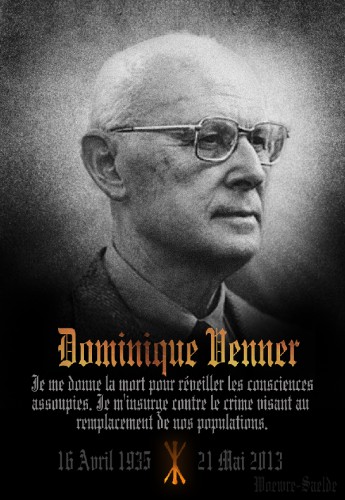

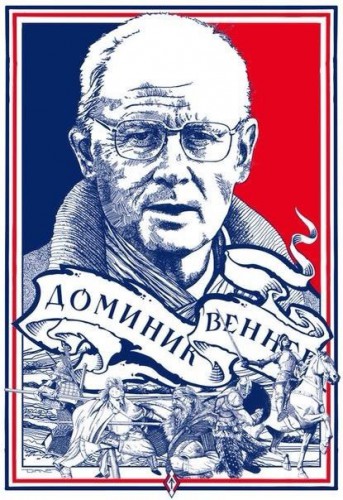

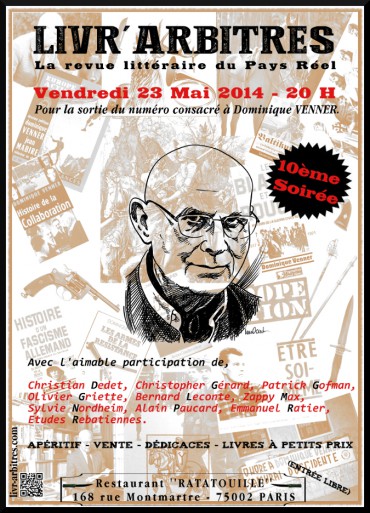

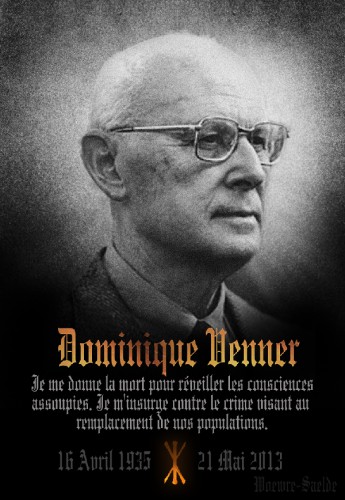

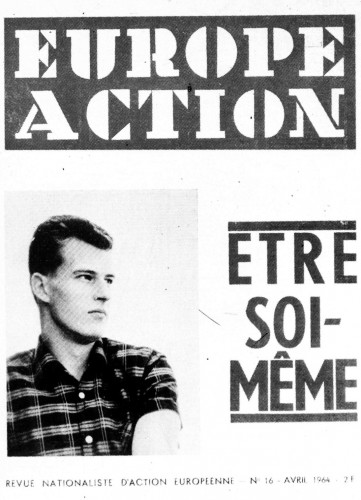

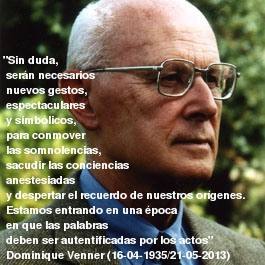

The French “nouvelle droite” acquired a worldwide reputation after a team around Jean-Claude Valla could manage in the autumn 1978 to man the redaction of a new and broad dispatched weekly magazine, the “Figaro Magazine”. Alain de Benoist was among the new journalists selected and took over the “rubrique des idées” (the “ideas’ column”) he already had run in the Figaro daily paper’s literary supplement, which was issued every Sunday. Louis Pauwels, the head of the new weekly “Figaro Magazine” and former chief animator of the “Groupes Planète” had accepted the deal proposed by the young wolves within the GRECE-team that proceeded from small national-revolutionist groups, students’ associations and tiny political parties that had failed to score sufficiently during several rounds of general or local elections in the Sixties. They all formerly were more or less linked to the monthly magazine “Europe-Action” mainly supervised by Dominique Venner. The events of May 1968 proved that the left or all the leftist non communist caucuses had actually seized the cultural or metapolitical power in France and elsewhere in Western Europe. Nowadays many studies tend to demonstrate that the American OSS and later the CIA had created artificially the 68 uprising in order to weaken Germany which became at the end of the Sixties an economical and industrial power again and to weaken also France which under De Gaulle became a nuclear military power having developed a competitive aircraft industry (Bloch-Dassault with the celebrated Mirage fighters that had been sold to Israel, India, Australia and Latin American countries as well as to some European countries such as Belgium). But in a first step the purpose of the metapolitical fight was to criticize and to suggest a counter-power to the 68 ideology as well as to defeat the heavy influence the communists still had in the French press at that time. This brought the “nouvelle droite” in a kind of precarious balance as, on the one hand, they still had columns in “Valeurs actuelles” and “Le Spectacle du monde”, which were publications owned by the press magnate Raymond Bourgine, who was an Atlanticist, and as, on a second hand, they had started to develop a thorough criticism of American values in both their separate home magazines “Nouvelle école” (1975), under the brilliant intellectual leadership of the Italian Giorgio Locchi, and “Eléments” (1976) under the vigorous supervision of Guillaume Faye.

Other ambiguity: Pauwels within the network of the “Groupes Planète” had staunchly supported some social criticism of the pre-68 movement and stressed the importance of the more or less Nietzschean notion of “one-dimensional man”, as a possible aspect hic et nunc of the “Last Man blinking his eye” whose deleterious influences one had to fight against, as well as the notion of an “Eros” able to wipe out all the petty consequences of a hyper-civilized and hyper-rationalized Western world, both notions having been theorized in Herbert Marcuse’s main books in the Sixties; now, in the columns of the brand new glossy “Figaro Magazine” (or abbreviated: “FigMag”), all the effects of the pre-68 and genuine 68 movement were submitted, with the help of the formerly marginal “pre-new right” would-be journalists, to a thorough criticism leading to a final and total rejection, in name of a new conservatism aiming at preserving the values of the West or at least of Old Europe. More than one theoretical gap between these discrepancies were not filled, leading in the four or five following years to a quite large array of misunderstandings. The eternal problem of lack of time couldn’t solve these discrepancies, leading at the end of 1981 to a clash between de Benoist and Bourgine, then to a recurrent blackmailing of Pauwels, who was threatened by attrition in the way advertisement agencies refused to place ads in the weekly FigMag. The constant blackmail Pauwels underwent aimed at sacking the “New Right” people and at throwing them out of the “Figmag” for the sole benefit of the exponents of the new ideological craze, coined by the system’s agencies: neo-liberalism.

A Russian “New Right” cannot be of course a tributary of all these Western European aspects of a general conservative-revolutionnist criticism of the main modern ideologies or political systems. A Russian “New Right” must of course be an original and independent stream, a synthesis of Russian ideas. According to the German Slavist Hildegard Kochanek, the Russian source of a general conservative revolutionist attitude lies of course in the Slavophile tradition, taking into account values like “potshvennitshestvo” and “samobytnitshestvo”, i. e. the roots of the glebe and the genuine political sense of community (“Gemeinschaft” in German). This implies, still according to Mrs. Kochanek, a kind of socialism, very different than the historical dominant forms of socialism within the 1st, 2nd and 3d Internationals, the West-European social democracies or the Soviet communism. Mrs. Kochanek sees Vladimir Soloviev and Sergej Nikolaïevitch Bulgakov (1871-1944) as the spiritual fathers of a spiritualized socialism, inspired by the very notion of Greek-Byzantine Sophia. Bulgakov, as an émigré in Paris, in the Twenties and Thirties, was clearly conscious of the lack of ethics in the several forms of real existing socialisms or communisms. Sophia and ethics help to break the vicious effects of “economical materialism” of both communist and social democratic doctrines, which are in the end not fundamentally different from the utilitarian Anglo-Saxon bourgeois ideology (“burzhuaznost”), as it was theorized by Jeremy Bentham and later by David Ricardo. Society, according to Bulgakov, cannot be seen as a mere mechanism of individual atoms trying to realize their own petty interests. In fact, Bulgakov produced long before the existence of a “New Right” a complete critique of the Western ideologies, that Guillaume Faye tried to formulate again —but this time in a non Christian intellectual frame— in his very first articles on “Western Civilisation”, published in “Eléments” in 1976, as well as in several articles and short essays about economical theory (but the main book Faye wrote about his views on economics was thrown into the wastebasket by de Benoist… I could only save some pages that I published in my “Orientations”, Nr. 5; the rest was spoilt by Faye himself, who used to clean his pipe with the scattered sheets…). In the former Soviet Union, Mikhail Antonov wrote some articles in 1989 in the well-known Moscovite journal “Nash Sovremennik”, urging the Russian economists not to adopt the Western unethical forms of economics but to continue Bulgakov’s work (see: Hildegard KOCHANEK, Die russisch-nationale Rechte von 1968 bis zum Ende der Sowjetunion – Eine Diskursanalyse, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, 1999); in the eyes of Bulgakov, it is impossible to let economics not be counter-balanced by ethical brakes. Without such “brakes”, economics tends to invade the whole sphere of human activities and to destroy all other factual, intellectual or spiritual fields in which mankind is evolving. Hypertrophy of economics leads to an extreme “fluidity” of human thoughts and actions: as Carl Schmitt explains it in his posthumous “Glossarium”, we aren’t Roman surveyors anymore but seamen writing “logbooks”. He meant that we have lost all links with the Earth.

So we expect to learn more about Russian ideas through a totally independent Russian “New Right”, that wouldn’t in no respect imitate Western models.

When you ask me who are the leaders or the leading personalities of the Western European New Right, I will have to enumerate country by country the men who were and are the main exponents of this diversified ideological current. I’ll only select France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Austria. In France, the leading personality is of course Alain de Benoist, who seems to personify the movement in its wholeness. According to Pierre Chassard the core group that intended at the very beginning to launch a metapolitical struggle and to spread “other ideas” than those in power was a college of friends, was mainly built by old members of “Europe Action” or the “Fédération des Etudiants Nationaux”, or even people having tried initiatives in the Fifties. They selected some younger collaborators. Alain de Benoist was among the members of this new generation: he had been selected because he had made good synthesized reviews of books and magazines and had coined well balanced definitions for “L’Observateur Européen”, a bulletin which was at the same time the heir publication of the “Cahiers Universitaires”, the intellectualized publication of a students’ association (FEN – Fédération des Etudiants Nationaux), and later a supplement to Dominique Venner’s monthly “Europe Action” (“Europe Action Hebdomadaire”). After Venner resigned in July 1967, a team decided to abandon pure politics and opt for metapolitics: this was the very birthday of “Nouvelle école”, the wonderful magazine that seduced me six years later in 1973, when I was only seventeen. But next to the first emergence of what will become the still existing “New Right” as a later expression of the prior “Nouvelle école” redaction, Domnique Venner started the “Institut d’Etudes Occidentales” and a bulletin called “Cité-Liberté”, but the experience only last a year and a half (from November 1970 till July 1971).

Later, some people hoping for a more active approach created the G.R.E.C.E.-Groups, more or less along the same organizational lines as Louis Pauwels’ “Planète-Groups” in the Sixties, with a representative group in every important town; these groups were supposed to start a “cultural revolution” to get rid of the conventional post war liberal ideology and its “translations” in real life; for the “Grecists”, their similar town-based groups would be called “unités régionales”. These metapolitical groups had as a purpose to organize locally speeches, debates, conferences, seminars or art exhibitions to compete with the dominant ideologies. To inform the members of these new created network, a bulletin called “Eléments” was launched, very simple in its layout: it was a plain pile of sheets wrapped in a light cardboard cover. In 1973 it became a full magazine, not only designed for the members but for a broad public. Both magazines made Benoist’s reputation in and outside France. For me all positive aspects of Benoist’s initiatives are directly linked with “Nouvelle école”. Later Guillaume Faye, a figure of a new “Grecist” generation, gave an energetic punch to “Eléments”. We may say after four decades of observation that the soul having animated “Nouvelle école” is undoubtfully Alain de Benoist and that all his other initiatives are either awkward adaptations to the Zeitgeist or betrayals of the core message of the initial movement from which he proceeds.

I mean here that the birth of metapolitics at the end of the Sixties was a clear and harsh declaration of war against the dominant metapolitical powers and against all the political systems and corrupted personnel they support: the very aim of metapolitics is to let appear the dominant power as a full illegitimacy. In such a long lasting war you cannot make compromises, you never criticize positions you once adopted, you never negate what you once asserted. On the contrary you have to spot immediately the new pseudo-intellectual garments the dominant power is regularly putting on, each time when its usual instruments aren’t fully efficient anymore; this spotting job is absolutely necessary in order not to be trapped by the new seducing strategies the foe is trying to spread to fool you, according to the principles once invented by Sun Tsu. You cannot criticize positions you once opted for, as if you had to be forgiven for youth mistakes, because you lose then rather large parts of your operation field. If you reject, for instance, biology or biohumanism or biological anthropology (Arnold Gehlen) or all types of medical-biological questions, because you could eventually be accused by the press to be a proponent of a new kind of “biological materialism” or of a “zoological view of mankind” or of “racialist eugenics”, etc., you’ll never be able anymore to suggest a well-thought national health policy programme elaborated by doctors, who intend to develop a preventive health system in society. That’s what happened to poor de Benoist, who was scared stiff to be labelled a “Nazi eugenist” since the very first polemical attack he underwent in 1970, an attack that wasn’t lead by the left as such but by Catholic neo-royalists, who had purposely adopted a typical leftist phraseology and created an ad hoc anti-racist committee to crush the future “New Right” team they saw as competitors in the new metapolitcal struggle that was about to be fought in France in the early Seventies.

Some years later Alain de Benoist interviewed for “Nouvelle école” the Nobel Prize Konrad Lorenz who had written well shaped didactical books to warn mankind of the dangers of a possible “lukewarm death” if the natural (and therefore biological) predispositions of Man as a living being were not taken into consideration by the political world or the Public Health Offices. Although he had the backing of a Nobel Prize winner and of the Oslo or Stockholm jury having granted Prof. Lorenz the Prize, de Benoist has till yet feared to resume the kind of research “Nouvelle école” had tried to start in the middle of the Seventies. The paralysing fear he felt in the deepest of his guts lead him to express all kind of denials and rejections that were in no case scientifically or factually established but were mere makeshift jobs typical of political journalists manipulating blueprints in order to deceive their audience.